*Author gives a long blast on the whistle, crosses her arms overhead and slow draws a box in the air. She pats her chest.*

“Hi Hockey World News, this is a self-referral. I’d like to know if there’s any reason why we can’t continue with video umpiring.”

*Disembodied voice sounds from parts unknown*

“I’ll have a look for you.”

From its inception as a trial in the 2006/2007 EHL season to its most recent iteration at the 2018 Commonwealth Games, video referral has evolved into both an essential

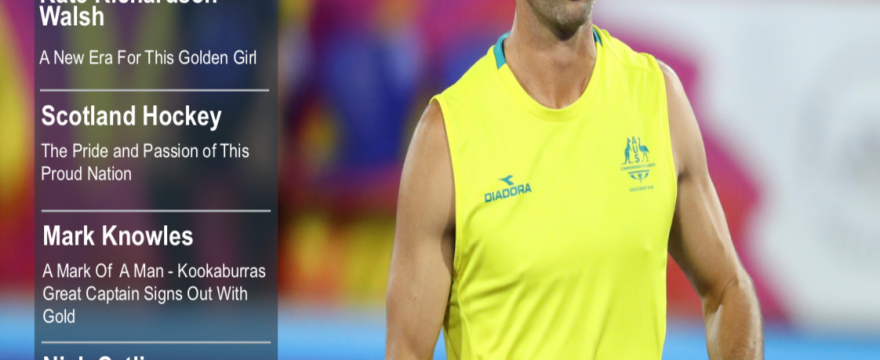

Through all the changes to the regulations over the past ten years, the controversy swirling around referral decisions seem to be ever-present. Top players such as Jamie Dwyer back in 2009 were highly

Still, on the whole, most of the hockey family agrees that the advent of the video referral has been positive for the game. Video umpire specialist and retired Olympic and World Panel umpire Carol Metchette (IRL) notes that “the biggest strength of VU is to prevent major errors that can be game-changing and gives reassurance to teams and umpires that the correct decision will be made. I loved being able to support the teams and umpires in this way.” She uses the past tense because recently the FIH Umpiring Committee announced that the role of the dedicated video umpire would be shut down due to budgetary concerns and pitch umpires will rotate into the position at upcoming competitions such as the Pro League.

For Trinidad & Tobago's Ayanna McClean, who was one of the first active FIH umpires to serve as a dedicated VU when she umpired at the HWL Semi-Final in Valencia, there's a flip side to this coin. “There can be an element of dependence on it and using it against players. Some umpires even come across as defensive and feel unsure about themselves if they have too many in a game. Personally, it can be a bit distracting, as I sometimes think about what, why, how I missed the call, during the game.” Taking it one step further, retired Dutch superstar Rob Reckers recently made a case for abolishing video review entirely due to negative impacts he perceives on umpires. Respect is earned and can only be done so based on both the efforts and umpires' human failings, he argued, and deferring decisions to video takes away from the human on the pitch.

One of the thorniest issues revolves around the highly subjective nature of many of the umpires' decisions–a feature (not a bug!) built right in our rather brusque rulebook. Inside and around the circle, an umpire will assess posture, positioning, the context of the play, body language, and variety of other subtle cues to deliver a split-second team penalty which can range from a free hit outside to a penalty stroke. Even these decisions are now put under the referral microscope.

At the Commonwealth Games, one such review came from the Indian men who wanted a free hit given outside for a back stick upgraded to a penalty corner as an intentional foul. Much to the surprise of the commentating team and many at home, the referral was successful. Canada's Tyler Klenk was there doing his second tournament combining pitch and booth roles and explains the problem:

One of the most challenging aspects of being a VU is giving decisions on interpretations (for example danger). A question of “foot or no foot” is simple to determine with the right shots and angles from the cameras. It's far more difficult to give an interpretation decision. When an umpire blows for danger, it's often because of a gut feeling you have about how dangerous a particular sequence is as it unfolds in front of you. Slow motion replays do not do much justice, as they often make plays appear worse than they actually are. Instead, it's equally vital for the VU to see the replay in real-time to get a full sense of the umpires on-field decision.

Tyler Klenk (CAN)

The flipside of gauging intention is when

Individual decisions aside, there are questions surrounding how we present referrals on broadcasts. Hockey fans may remember the 2017 Rabo EuroHockey Championships in Amsterdam as a “golden era” in video umpiring, if an era can last ten days, with England's Andy Mair was appointed to the booth. His explanations of decisions were concise and yet much more thorough than the cursory “no reason to change your decision” script that we often hear.

These descriptions had a double-pronged effect, according to Mair, who had extensive experience as a World Panel and Olympic umpire before retiring and taking to the dedicated VU role. Not only would the pitch umpire receive enough information that they could pass along the details of the decision to the player referring the question, but it provided exceptional clarity to viewers around the world. “The commentating team of Nick Irvine and Simon Mason were very keen to learn, and that helped them pass along the nuances of the decisions to the fans,” he says. Further, this education pays long-term dividends as the broadcast team's talent are then better versed in what umpires are looking for and can inductively puzzle through future controversial decisions. When they share their better-informed analysis out loud, that knowledge spreads throughout the entire hockey community.

All this does sound like a lovely utopia, but it's not as easy as just instructing “have flair like Mair” in a video umpiring briefing.

Mair describes one of the challenges of implementing a unified approach to presenting the video referral is the umpiring team isn't aware of what the broadcast setup will be until they arrive at a tournament, and perhaps not even until the first match is underway. This can mean that their participation in the broadcast will vary the spectrum from their audio being fed only to the pitch umpires, to their audio and video of themselves in the booth being shared over not only the broadcast but to the fans in the stadium, to everything in between. The discussions needed to reach a cohesive approach are impossible to have in advance, and so the approach taken by video umpires may necessarily evolve over the course of a tournament. When umpires rotate into the booth from on the pitch, they may not have the opportunity in one or two matches to hone their presentation style to match what VUs with dozens of opportunities have developed.

Moreover, not every umpire is cut out for the role. Metchette warns, “it’s a more difficult job than people think. Some very experienced umpires are surprised when they do VU at first. Everything stops and they are waiting for your answer, and sometimes you have to be brave.”

In addition to the sudden fishbowl pressure, “video umpiring calls upon a specific skill set

Does this mean that future umpires will be selected for international duty and promoted based on their on-field abilities as well as these other video review-specific qualities? How will that impact umpires who don't speak English as their first language? We'll see the introduction of a VUC (video umpire coach) at the Pro League; will this produce the quality and consistency from the VUs that the global streaming audience demands?

There are many positives to pull from these stories. Over ten years the scope of video referral has slowly expanded to take into account feedback from the teams, and that's reflected in positive reviews. “The feedback I heard from the players [at the 2017 Rabo EuroHockey Championship] in Amsterdam was that they love it,” Mair notes. Overall, it's another method which the third team uses in the pursuit of excellence in serving the game with accuracy and fairness, and will undoubtedly continue to improve over the next ten years.

*camera cuts back to the author on the pitch*

I have a decision for you: the FIH keeps their referral, and we can award a win for hockey!

(This article appeared in Hockey World News Edition 5, April 2018)